Freedom to Travel

Revitalizing Africa's Ecosystems with Wildlife Corridors

Isolation and Bottlenecks

Before humans built cities and roads crisscrossing the natural world, wildlife had the freedom to roam. Their movements were guided by their needs – where was the best food, the most water, the safest birthing grounds? Another important benefit of freedom to move is keeping diversity in the genetic pool. (The genetic pool is all the individuals of mating age.) By allowing individuals from different family lines to mix and breed, it keeps the population diverse and healthy. Without this mixing, closely related individuals will mate, allowing rare, harmful traits to surface. The longer this goes on the more harmful traits will appear, diminishing the health of the population. This phenomenon is called a genetic bottleneck – an apt name since it is the result of a shrinking breeding population. One of the biggest causes of a genetic bottleneck is geographic isolation from habitat loss, resulting in no inter-breeding.

Africa’s Managed Lands

In Africa, land is managed in several ways based on who’s in charge and what’s allowed – there are national parks, private concessions, and game reserves to name a few. What all of these land types have in common is that they are mere fragments of a once great and continuous landscape. This fragmentation means that wildlife cannot move freely between habitats for foraging, hunting, and breeding purposes. Habitat loss is happening at alarming rates due to agricultural expansion and human settlement. No matter how well managed a land fragment is, the resident wildlife can suffer if there is not enough genetic mixing in the population. Wildlife doesn’t understand borders, and countless animals have fallen victim to car strikes, poisoning, or being shot when they wander through developed areas. Nature is resilient and wildlife can normally withstand the pressures of habitat fragmentation, but human conflict can act as the final nail in the coffin of a population walking the line between okay and endangered.

Regrowing Africa’s Edens

With numerous pressures on Africa’s wildlife, reconnecting fragmented habitats could offer a much needed boost to their welfare. It would restore their ability to roam freely, moving between regions in their perpetual search for a better habitat. Beyond that it would give wildlife the space to move away from any threats, such as bush fires, droughts, and pressures from civilization.

But how do you reconnect fragmented habitats? With wildlife corridors! A wildlife corridor is a swath of protected land that reconnects two formerly connected areas. The key is that the land is in a wild state, providing safe passage for wildlife to move freely. With time the overall health of the newly reunited ecosystem will improve and restabilize. Another huge benefit is that wildlife can move away from any human-wildlife conflicts that may occur on the fringe of their habitat.

Wildlife corridors seem like such a simple idea in theory but the execution is riddled with challenges. Where does the land come from? Who will manage and protect it? Is it a worthwhile investment for the long-term? In all three of these dilemmas, the local community is key to finding a solution. Not only is the tract of land often patched together from land leased from the local community, but they are also involved in the long-term stewardship of it. They work with those already managing the soon-to-be connected regions, creating a cohesive management scheme that benefits both the wildlife and the local communities through sustainable tourism and conservation jobs. Allowing the land to return to a natural state is a slow process that takes continued community support. Ecosystems are complex and need time to reestablish, especially if it is going to act as a safe haven for wildlife. It may be a few years or a few decades depending on the ecosystem in question. Rainforest could take twenty years before it's suitable for chimpanzees, but savannah grasslands may only take a few years before it can support migrating grazers. Throughout this rewilding process, careful and dedicated stewardship is essential.

Amboseli, Chyulu Hills & Tsavo West

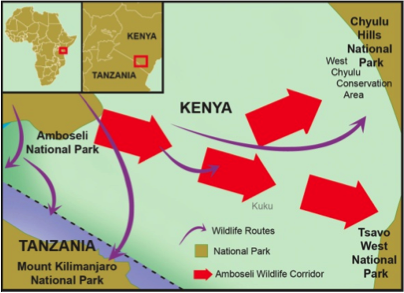

In the beautiful hills of southern Kenya, the African Wildlife Foundation is reestablishing a wildlife corridor from the Amboseli region to the Chyulu Hills and Tsavo West National Park. AWF is working with the local communities to set up a series of conservancies on leased lands. It is slowly rewilding and in the process reopening historic migration routes for elephant, giraffe, lion, zebra, cheetah, and countless others. Already considered a great success, this corridor should guide future conservation projects.

There may be many challenges in establishing wildlife corridors, but they are a key part of Africa’s future. Pristine wilderness is a precious resource, and nowhere else has wilderness quite like Africa. The wildlife is unsurpassed, the landscapes are breathtakingly beautiful, and the sunsets are unrivaled. Wildlife corridors offer hope for protecting Africa’s wild heart by cultivating healthy ecosystems and supporting its beautiful biodiversity.